Our history

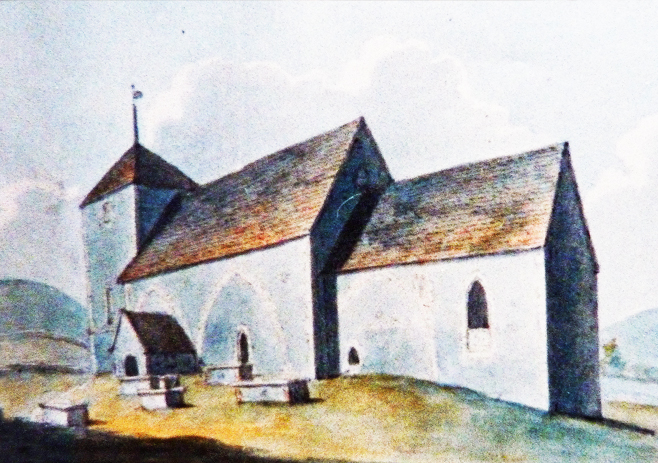

Our “little church”

Almost hidden by trees, Saint Wulfran’s Parish Church nestles into a steeply-rising, east-facing slope of the South Downs, just over half-a-mile from the sea at Ovingdean Gap. It is believed to be the oldest building within the bounds of the city of Brighton and Hove.

It has been here for at least a thousand years: nobody knows exactly how long, but it is mentioned in Domesday Book – an “ecclesiola” or “little church”. There was probably a Saxon church on the same site before the present church was built, but it is likely that the Domesday Book record refers to a new construction built by the first Norman Lord of the Manor, Godfrey de Pierpoint, sometime in the period 1066-86. This building would have originally consisted of the nave and chancel: the bell tower was added in the early 13th century.

Changes

In all probability there were few significant changes over the centuries until the early nineteenth century, when John Marshall became the first rector of modern times actually to live in Ovingdean. Before then there were absentee rectors, and services were conducted by poorly paid curates who lived in what an 18th century Bishop of Chichester described as “a mean thatched parsonage, and only proper for a labouring man to live in”.

Marshall built the Rectory in Greenways in 1805, an imposing residence which was sold by the Church of England in 1976. He also carried out extensive repairs and alterations to the church and installed box pews, replacing old and decaying benches. While he was rector he appointed his son as curate, and built for him in 1825 the house next to the church known as Rectory Cottage.

A major programme of reconstruction and renovation was carried out under the rectorship of Alfred Stead in the 1860s. At this time Marshall’s box pews were replaced with the present bench seating.

The chapel was added in 1907, electricity was installed in 1939, and the vestry and organ loft built in 1984.

St Wulfran

There is no record of why or how the church came to be dedicated to St Wulfran. The dedication could have been at any time, even going back to the days of the original Saxon church. Ours is one of only two churches in England dedicated to this saint, the other being at Grantham in Lincolnshire.

There are few known facts about the life of St Wulfran, and a lot of legend. He was a French priest who became Archbishop of Sens, and later resigned to become a missionary. While engaged on missionary work he met and worked with the English St Willibrord and other English Christians.

He set out to convert the people of Frisia, now part of Holland, who were then still pagan. A story about Wulfran tells how he miraculously saved the lives of children in Frisia who were about to be sacrificed in pagan rites. He ended his days in the Benedictine Abbey at Fontenelle in France.

For more information see “A visitor’s Guide to St Wulfran’s Church” available in the church

The Churchyard

Memorials to prominent people in St Wulfran’s churchyard

Some distinguished people have been buried and commemorated in Ovingdean. In the nineteenth century it became fashionable for wealthy people to be buried and commemorated in a country churchyard such as ours, rather than in a municipal cemetery in the town.

Sophia Jex-Blake (1840 1912)

Perhaps the most notable was Sophia Jex-Blake, one of the first women to be registered as a doctor in the United Kingdom. Her imposing family tomb is situated facing you as you enter the churchyard through the lychgate. She lived with her parents in Brighton as a teenager and at various other periods in her life, up to 1879. Sophia fought long and strenuously for the right of women to study medicine, be awarded University degrees, and practise as physicians. She was involved in founding two medical schools for women, in London (1874) and in Edinburgh (1888), as well as the Hospital for Women and Children in Edinburgh (1886).

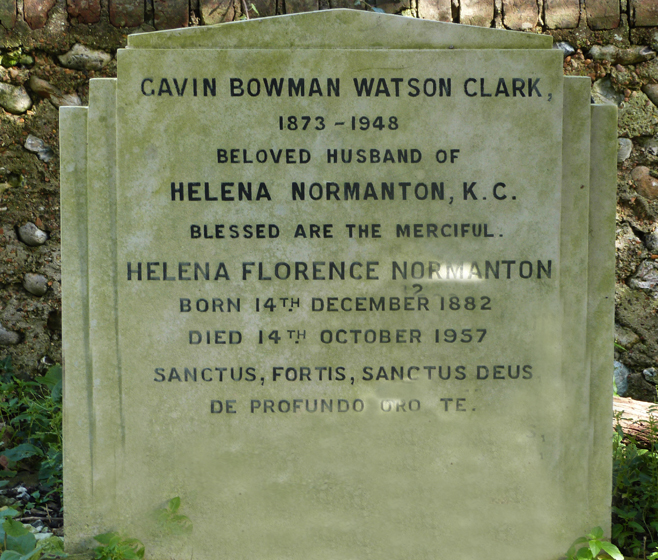

Helena Normanton (1882 – 1957)

A more modest headstone commemorates another distinguished woman, Helena Normanton, the second woman to practise as a barrister in England. She is buried in the south-east corner of the old churchyard a tree near the wall dividing the churchyard from the Old Rectory.

She was the first woman to appear as a barrister in the High Court and the Old Bailey, and one of the first of two women to be made a KC. She grew up in Brighton and was a life-long champion of women’s rights.

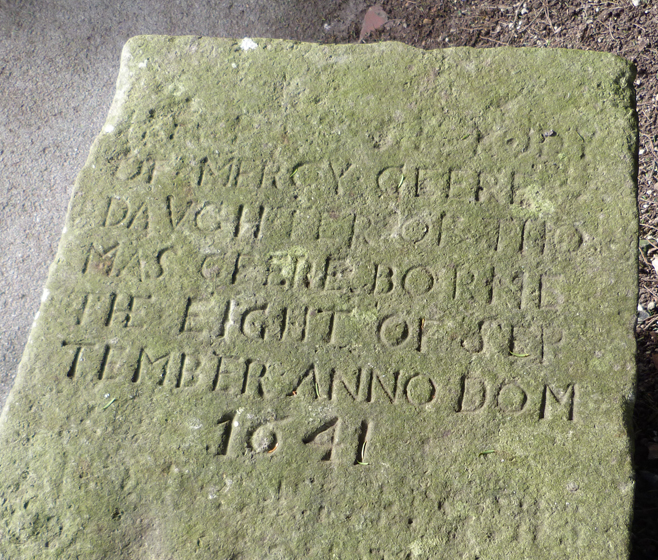

Mercy Geere (1641 – 1671)

Graves were not normally marked until the 17th century. The oldest marked graves in the church-yard are close to the church door under the yew tree, to the right of the door as you enter, and commemorate the Geere family. They were a prominent local farming family who lived in the Grange, opposite the village green. The oldest gravestone is inscribed to the memory of Mercy Geere, daughter of Thomas Geere.

Charles Kempe (1837 – 1907)

One of the more imposing tombs is that of the Kemp family, just opposite the church door. Nathaniel Kemp built Ovingdean House (Now Oxford International College) in 1792, and lived there until his death in 1843. His son Charles started in business 1866 as the Kempe Studio for Stained Glass and Church Furniture, and was heavily involved in the refurbishment of St Wulfran’s church, completed in 1867. He designed the chancel ceiling and eleven of the stained glass windows in the church.

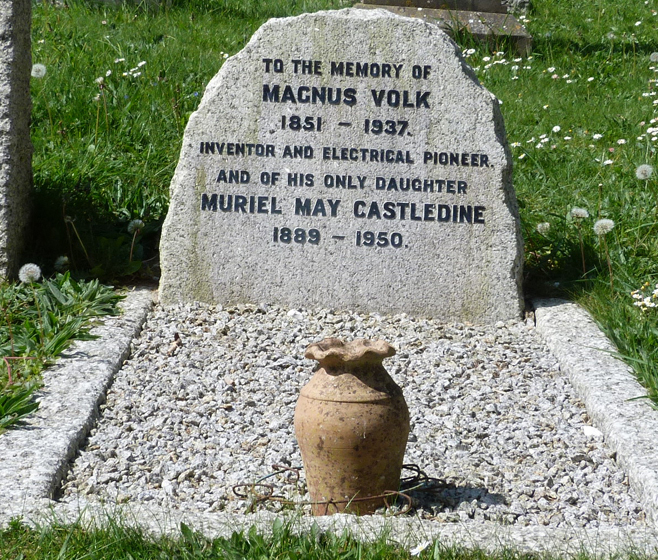

Magnus Volk (1851 – 1937)

Perhaps the best-known of all those buried here is Magnus Volk, whose modest gravestone is on the left just past the steps. He was an engineer and inventor, who in the 1880s built several electric cars, and was the first person in Brighton to light his house with electricity. He built in 1883 the electric railway which ran originally from the pier to Paston Place. It is the oldest electric railway in the world still operating. He also built in 1896 the short-lived extension to Rottingdean, nicknamed “Daddy Longlegs”, whose rails ran along the shore, under water at high tide.

For more detailed information, there is in the church a leaflet on memorials available to take away.

The Kempe Ceiling

Charles Eamer Kempe (he added the ‘e’ in his thirties) was the fifth son and youngest of seven children of Nathaniel Kemp (1759-1843) of Ovingdean House. The Kemp family were a wealthy and important land-owning family around Brighton and Lewes in the late 18th century. They were descended from an old Saxon family that produced John Kemp(e) (1308?-1454) who was Lord Chancellor and Archbishop successively of York and Canterbury. As a young man Charles wanted to enter the church but thought his speech impediment would be a drawback. Instead he studied architecture and learned the techniques of stained glass. Having inherited a substantial income at 21 from his father’s will, Kempe started the ‘Kempe Studio for Stained Glass and Church Furniture’. This was a very successful venture and the studio was responsible for 3,141 windows from 1869 to 1907.

His first independent commission was the astonishing ceiling in St Wulfran’s chancel.

The restoration of this ceiling by Ruth McNeilage and team took place in October 2005.

The painted ceiling is chief among the art treasures in our church. It was designed by Charles Kempe in 1867 to commemorate his father Nathaniel Kemp, who lived in Ovingdean Hall where Charles was born in 1837, and who was churchwarden at St Wulfran’s for many years.

The decorated ceiling also celebrated the completion of a major restoration of the church in that year. Although the church dates from the 11th century and is listed grade 1, little is known of its history until the 19th century, when two major restoration projects were carried out, the first at the beginning of the century and the second in the 1860s during the rectorship of the Revd Alfred Stead (1844-89). Substantial structural repairs were carried out at this time to the outside of the building, and inside the old box pews were replaced by the present-day pews, sash windows were removed and replaced with windows more in keeping with the medieval style, and the tower area re-opened to provide additional seating.

Charles Kempe’s decoration is painted directly on to the wooden barrel-vaulted ceiling. It consists of trailing floral designs of leaves and flowers, interspersed at regular intervals with a dove holding a scroll, inscribed with the word “alleluia”.

Kempe also designed a number of stained glass windows in the church, as well as the carved wooden reredos and rood.

Charles Kempe was heavily influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement and by the work of his contemporaries William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, in harking back to a romantic medievalism in his designs. Their ideals had much in common with those of the Anglo-Catholic movement developing within the Church of England at that time, and his work is of considerable significance in the development of Victorian church art and decoration.

He commenced in business on his own account in 1866, and it is probable that his work for St Wulfran’s was his first commission. He eventually became one of the most sought-after and successful designers of stained-glass windows and church furnishings of his day. At the height of his success, towards the end of his life, he was commissioned to produce a window of St George for Buckingham Palace.

Kempe died in 1907 and was buried in the family vault in St Wulfran’s churchyard.